The Science of Ink Flow: Ballpoint vs. Rollerball vs. Gel

The humble writing instrument, often dismissed as a simple commodity, is in fact a marvel of applied material science and precision engineering. From the perspective of a Material Engineer, the fundamental difference between a ballpoint, a rollerball, and a gel pen lies not merely in their aesthetic or price point, but in the highly specialized rheological properties of their respective inks and the tribological design of their writing tips. The selection of materials—from the tungsten carbide ball to the polymer matrix of the ink—is a complex optimization problem balancing flow, drying time, permanence, and manufacturing cost.

The Rheological Imperative: Viscosity and Shear-Thinning

At the core of pen performance is the science of rheology, the study of the flow of matter. Ink is a non-Newtonian fluid, meaning its viscosity—its resistance to flow—changes under stress. This property is deliberately engineered to ensure the ink remains stable within the reservoir but flows instantaneously and consistently when the pen tip is applied to paper.

The classic ballpoint pen utilizes a highly viscous, oil-based paste ink. This ink is typically thixotropic, a specific type of shear-thinning behavior. When at rest, the ink's high viscosity prevents leakage and premature drying. However, the shear stress generated by the rotation of the ball against the paper and the socket causes the ink's internal structure to momentarily break down, drastically lowering its viscosity. This allows a thin film of ink to transfer onto the ball and then onto the substrate. The viscosity of ballpoint ink can range from 10,000 to 20,000 centipoise (cP) at rest, dropping to a mere fraction of that under the high shear rate of writing. This high initial viscosity is the primary reason ballpoint pens require more pressure to write than their counterparts.

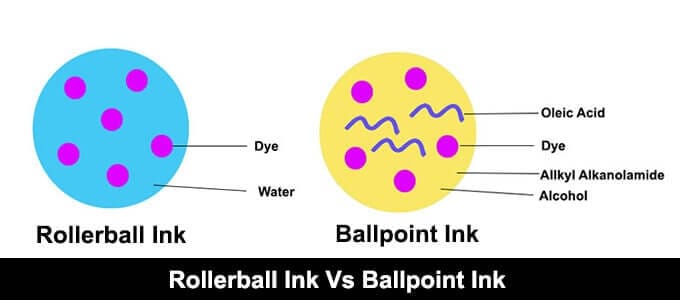

In contrast, rollerball and gel inks operate at significantly lower viscosities. Traditional rollerball ink is water-based and behaves closer to a Newtonian fluid, with a viscosity typically between 100 and 1,000 cP. This lower viscosity facilitates a smoother, more fluid line with minimal pressure, relying on a sophisticated capillary feed system to control flow and prevent blotting. Gel ink, while also water-based, introduces a polymer network—often utilizing compounds like xanthan gum or other polysaccharide thickeners—to create a viscoelastic gel structure. This structure allows the ink to suspend pigment particles (a key differentiator from dye-based rollerball inks) and exhibit extreme shear-thinning. At rest, the gel's viscosity is high enough to prevent pigment settling and leakage, but the moment the ball rotates, the polymer chains align, and the viscosity plummets, allowing for a rich, smooth flow.

Ballpoint Engineering: The Tribological Challenge

The ballpoint mechanism is a triumph of tribology—the science of friction, lubrication, and wear. The writing tip consists of a tiny, spherical ball, typically 0.5 mm to 1.2 mm in diameter, seated in a precisely machined socket. The material of choice for the ball is almost universally tungsten carbide (WC), a ceramic composite known for its extreme hardness (approaching 9 on the Mohs scale) and wear resistance. Stainless steel is sometimes used for lower-cost options, but its inferior hardness leads to faster wear and less consistent line width over time.

The socket itself is usually brass or nickel silver, chosen for its machinability and corrosion resistance. The clearance between the ball and the socket is critical. If the gap is too large, the highly viscous ink will leak or smear. If it is too tight, the ball will seize, or the ink flow will be restricted. Manufacturing tolerances must be held to within a few micrometers to ensure reliable operation. The oil-based ink not only carries the colorant but also acts as a lubricant for the ball, reducing friction and wear on the socket.

A key engineering challenge for ballpoints is the phenomenon of "skipping" or "starving." This occurs when the shear stress is insufficient to adequately thin the ink, or when the ink's internal structure fails to reform quickly enough after flow, leading to an inconsistent film transfer. Furthermore, the longevity of the ink is paramount. The solvent system—often a blend of glycols and oleic acid—must be carefully balanced to prevent premature evaporation, which would lead to the ink thickening and clogging the mechanism. For corporate clients procuring large volumes of pens, understanding the shelf life and storage conditions is crucial, a factor often overlooked in the initial design brief. This is particularly relevant when considering the procurement process, where factors like minimum order quantities (MOQs) for specialized components can significantly impact the final product's quality and cost. For a deeper dive into the economics of scale in manufacturing, one might consider the challenges of navigating MOQs in the supply chain.

Rollerball and Gel: Capillary Action and Pigment Suspension

The shift to water-based inks in rollerball and gel pens introduces a different set of material and fluid dynamics challenges.

The Rollerball System

The traditional rollerball pen uses a dye-based ink with a low surface tension, allowing it to be drawn out by capillary action through a fiber or plastic feed system. The ball in a rollerball is often stainless steel, as the lower viscosity ink provides less lubrication, and the ball's primary function is to simply roll and act as a valve. The lower viscosity results in a much darker, more saturated line, as more ink is deposited per unit area.

However, the use of water as the primary solvent presents two major material science hurdles:

- Corrosion: The water-based ink can be corrosive to internal metal components if not properly formulated with corrosion inhibitors.

- Drying: The high vapor pressure of water means the ink is highly susceptible to drying out, leading to clogging if the cap is left off. The pen's cap and sealing mechanism must be engineered with high precision to maintain a hermetic seal.

The Gel Ink Revolution

Gel ink represents a significant advancement, combining the rich color and smooth flow of a rollerball with the permanence and stability of a ballpoint's pigment. The material science here is focused on the pigment suspension. Unlike dye-based inks, which dissolve the colorant, gel inks use fine, solid pigment particles. These particles provide superior lightfastness and water resistance, making the writing more archival.

The challenge is keeping these heavy pigment particles evenly suspended. This is achieved through the aforementioned polymer network. The ink is a colloidal suspension, and the polymer acts as a stabilizing agent. When the pen is at rest, the yield stress of the gel is greater than the gravitational force on the pigment particles, preventing sedimentation. Only when the shear stress of writing is applied does the gel structure temporarily collapse, allowing the ink to flow.

What is the primary material science factor that dictates the difference in writing feel between a ballpoint and a gel pen? The primary factor is the rheological profile, specifically the difference in yield stress and shear-thinning behavior. Ballpoint ink has a high static viscosity and requires significant shear to initiate flow, resulting in a "drag" feel. Gel ink, conversely, has a high yield stress at rest to suspend pigments but exhibits extreme shear-thinning, meaning its viscosity drops dramatically under the low shear of writing, leading to a much smoother, "effortless" glide. This fundamental difference in how the ink responds to mechanical stress is what defines the user experience.

Performance Metrics: Line Density, Permanence, and Drying Kinetics

As Material Engineers, we evaluate these writing systems based on quantifiable performance metrics.

| Metric | Ballpoint (Oil-Based) | Rollerball (Dye-Based, Water) | Gel (Pigment-Based, Water/Polymer) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viscosity (Writing) | Medium-High (Shear-thinned) | Low | Very Low (Extreme Shear-thinning) |

| Drying Mechanism | Solvent absorption/evaporation | Rapid Solvent evaporation/absorption | Rapid Solvent evaporation/absorption |

| Line Density | Low-Medium (Thin film) | High (Saturated) | High (Opaque, Pigmented) |

| Archival Quality | Good (Oil-based stability) | Poor (Dyes fade, water-soluble) | Excellent (Pigments, water-resistant) |

| Smear Resistance | Excellent (Fast absorption) | Poor (Slow drying) | Good (Fast drying due to thin layer) |

| Pressure Required | High | Low | Low |

Drying Kinetics: The drying time is a critical factor, especially in high-speed writing or for left-handed users. Ballpoint ink dries primarily through absorption into the paper's cellulose fibers, followed by slow solvent evaporation. The high viscosity limits the amount of ink deposited, contributing to its excellent smear resistance. Rollerball and gel inks, due to their water base, rely on rapid evaporation and absorption. While gel inks deposit a thicker, more opaque line, their polymer structure allows for a thinner, more controlled layer to be applied compared to the free-flowing nature of a traditional rollerball, often resulting in a surprisingly fast drying time. This is a crucial consideration for any corporate entity that values a clean, professional signature on important documents.

Permanence and Archival Quality: For legal or archival purposes, the chemical composition of the colorant is key. Dye-based rollerball inks are soluble and susceptible to fading from UV light and washing out with water. Pigment-based gel inks, however, use solid color particles that are chemically inert and physically trapped within the paper fibers once the solvent evaporates. This makes them highly resistant to water and light, a factor that should weigh heavily in the selection process for high-value corporate documentation or gifts intended for long-term use.

Customization and Surface Interaction

The choice of pen mechanism also impacts the potential for customization, particularly when considering the material of the pen body itself. The pen body is the canvas for corporate branding, and the material engineer must ensure compatibility between the substrate and the decoration method. For instance, a metal-bodied pen designed for a high-end gel refill might be destined for laser engraving or UV printing, each requiring specific surface preparation and material composition to achieve optimal adhesion and aesthetic quality.

The interaction between the pen tip and the writing substrate (paper) is the final piece of the puzzle. The paper's surface energy, porosity, and fiber structure all influence the final line quality. A low-viscosity rollerball ink, for example, is prone to "feathering" or "bleeding" on highly porous, low-quality paper, as the ink spreads laterally through the fibers. A high-viscosity ballpoint ink is less susceptible to this, but may struggle to write smoothly on very glossy or non-porous surfaces.

In the Malaysian context, where corporate gifting often involves high-quality, branded stationery, the Material Engineer's expertise is vital. The tropical climate, with its high humidity, can affect the long-term stability of water-based inks, potentially accelerating corrosion or promoting mold growth in poorly formulated products. Therefore, the selection of ink additives, such as biocides and humectants, becomes a localized engineering necessity to ensure the product maintains its performance integrity from the moment it leaves the factory floor to its use in a pejabat in Kuala Lumpur or a remote site in Sarawak.

The engineering behind a simple pen is a delicate dance between fluid dynamics, polymer chemistry, and precision manufacturing. The ballpoint, rollerball, and gel pen each represent a distinct solution to the problem of controlled ink delivery, optimized for different performance characteristics. The Material Engineer's role is to understand these fundamental differences to ensure that the final product—whether a high-volume promotional item or a premium executive gift—delivers a consistent, reliable, and chemically stable writing experience that reflects the quality of the brand it represents. The subtle nuances in material choice and design tolerance are what separate a disposable novelty from a cherished, long-lasting instrument. The selection process for corporate gifts must therefore be guided by an understanding of these technical specifications, ensuring the gift aligns with the intended use and the recipient's expectation of quality, a principle that underpins sound corporate gifting etiquette.

The Future of Writing: Smart Materials and Nanotechnology

Looking ahead, the field is moving towards smart materials and nanotechnology. Research is ongoing into self-healing polymers for ink reservoirs and anti-clogging coatings for ball sockets. The goal is to further reduce the necessary writing pressure while simultaneously increasing the archival life and color saturation. Imagine an ink that instantly adjusts its viscosity based on the temperature and humidity of the environment, a truly adaptive writing fluid. This next generation of writing instruments will continue to be defined by the relentless pursuit of material perfection at the micro-scale. The pen, far from being obsolete, remains a fertile ground for innovation in material science.

Planning a Custom Notebook Project?

Check our detailed supplier capabilities guide to see what's feasible for your budget and timeline.